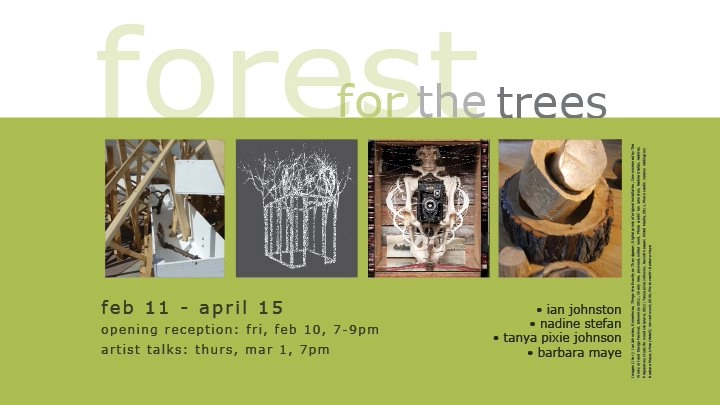

Forest for the Trees: Barbara Maye, Tanya Pixie Johnson, Nadine Stefan, Ian Johnson

Curated by Jessica Demers

Forest for the Trees brings together four regional artists whose work explores the interplay between nature and culture. A person who “can’t see the forest for the trees” focuses only on the details of what is right in front of her or him, rather than considering the larger context. Through diverse approaches and media, these artists invite us to contemplate our relationship to the natural world.

Trees are an enduring symbol of the life force in nature, and they play an important role in our physical lives. Barbara Maye investigates the stories of trees through recording the language etched in their grain and bark. Her carvings express the First Nations’ concept of the growth rings of trees representing the life stages of humans. Gallery visitors are welcome to (gently!) handle the books and re-arrange the wood pieces, discovering the trees’ histories for themselves.

Tanya Pixie Johnson works closely with the Sinixt people and has been given permission to express their traditional stories symbolically through her artwork. The chairs represent her role as a witness to the Sinixt culture, as well as the history of the homesteaders who lived along the shores of the Slocan and Columbia Rivers. Her work speaks to the spiritual dimension that lives within the physical realm and is reflected in our bodies and the landscape around us.

The act of preserving and documenting ecological and cultural history can be seen in Maye and Johnson’s work as well as in the piece, Sometimes, Things Are Exactly as They Appear, by Ian Johnston. His futile attempt at re-constructing a felled cherry tree humourously references how our ravenous appetite for natural resources is threatening our collective future. The tree becomes both a specimen, a monument of our failure to protect nature.

Nadine Stefan creates both tension and harmony between nature and the human-constructed environment in her piece, Habitat. By merging lumber with sapling branches, a linear, controlled and cage-like structure becomes seemingly renewed and filled with life. It also questions our definition of home, and whether we are living in our environment in ways that ensure the survival of ours and other species.

Like the land art movement of the 1960’s and the contemporary work of artists such as Andy Goldsworthy, these artists present refreshing approaches to making art about the natural environment that go beyond the traditional genre of representational landscape art. The increasing demand for Canada’s natural resources and the effects of climate change have altered our relationship with nature. Through their work, these artists encourage us to reconsider that relationship, and the effects of our actions upon the planet.