In Our Community: the History of the Nelson & District Credit Union and photographs by Fred Rosenberg

Curated by Deb Thompson

The show will feature a display of the history of the NDCU and a photographs from noted local photographer Fred Rosenberg selected from the collection of Touchstones Nelson. Among the interesting assortment of articles from the history of the NDCU are literature and slogans from the 1930-50s regarding the conception of cooperatives, Y2K crisis propaganda and vintage banking tools.

Credit Union Manager, Tom Atkins states, “Credit unions have a history of providing an alternative to banks by advocating equality, equity and mutual self-help. Since 1950 Nelson & District Credit Union has grown from a modest beginning with deposits in a cash box to a community cornerstone offering a range of financial services. In celebrating our 60 years as a community-based financial co-operative we hope this exhibit puts a face to the past efforts of the members and staff that have made our credit union the success that it is.”

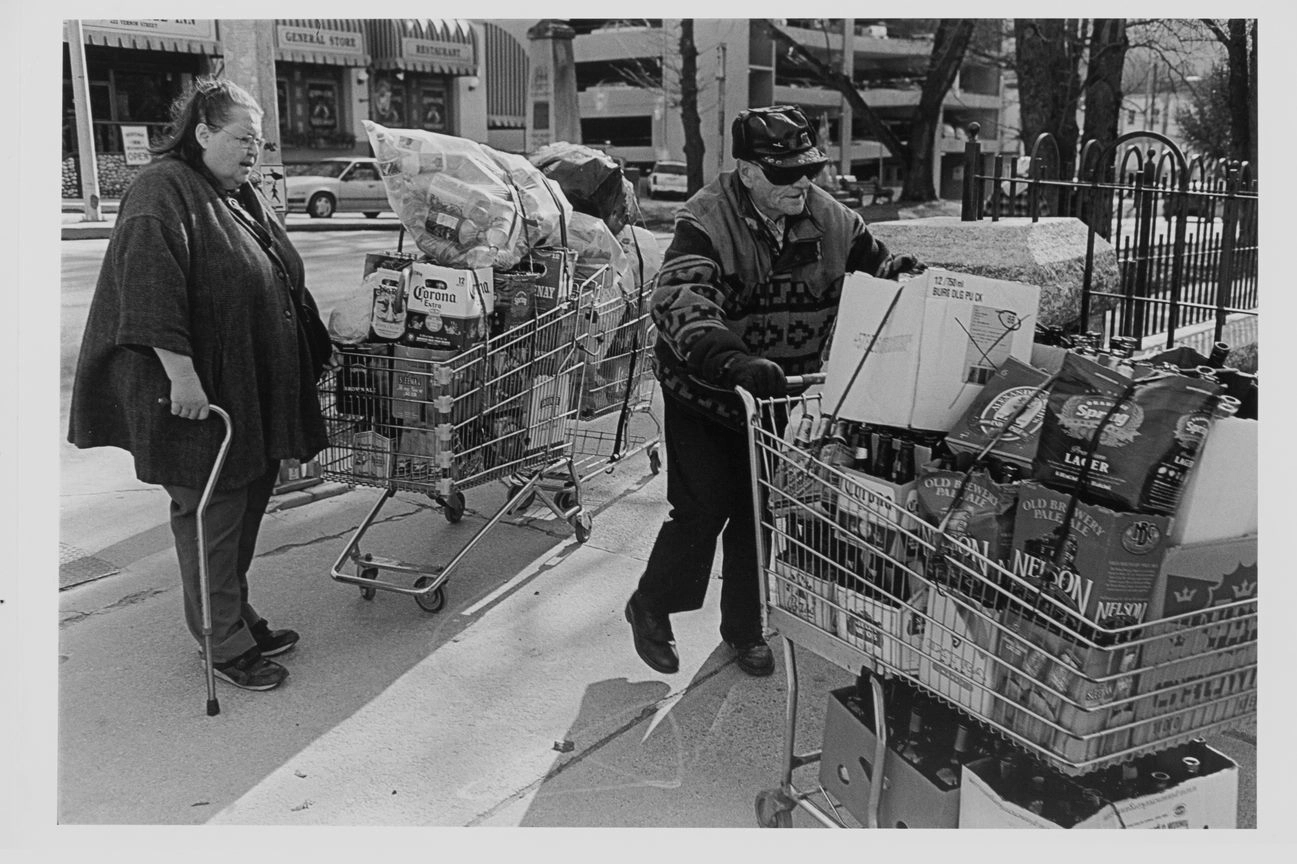

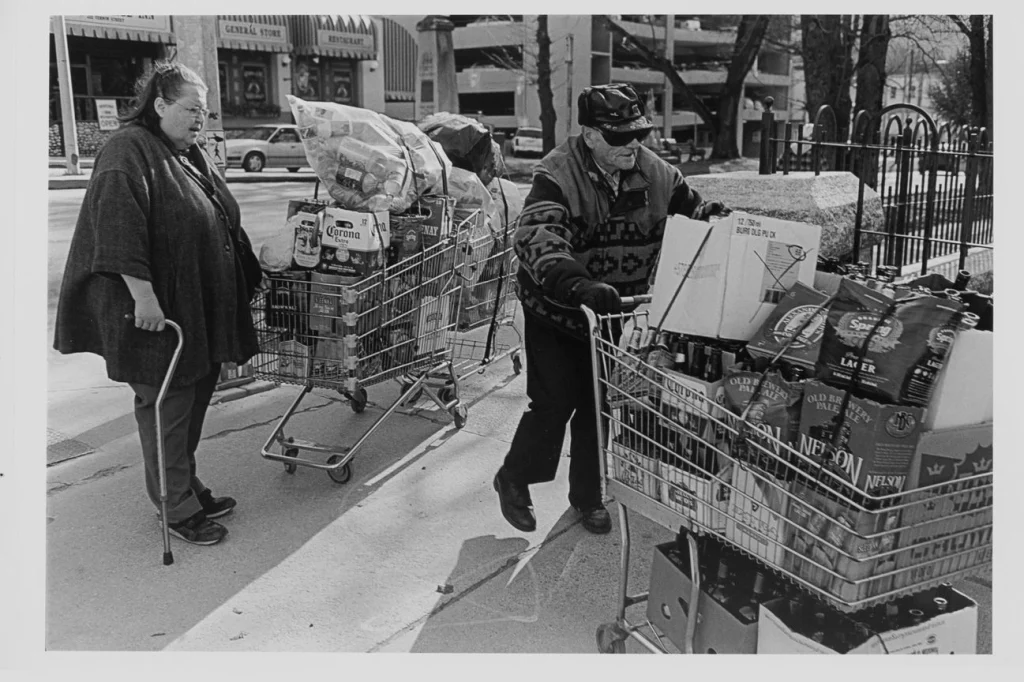

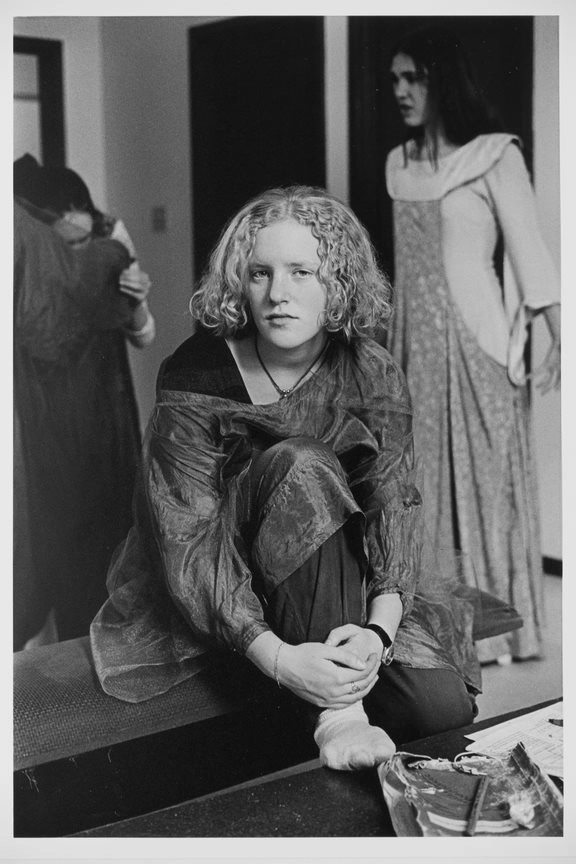

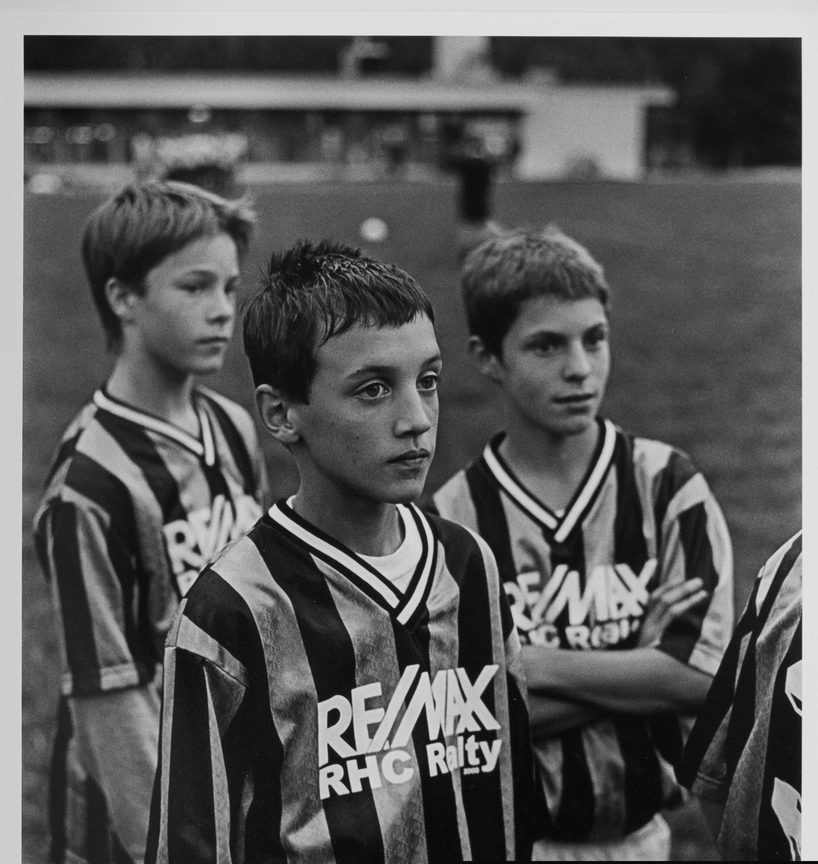

Fred Rosenberg’s black and white documentary portraits taken in Nelson between 1999 and 2004 show case the artists talent of capturing a candid moment in the lives of his subjects that reach beyond the personal to a universal expression of human nature.

Fred Rosenberg

Fred Rosenberg studied Photo-Journalism at San Jose State University in Northern California from 1964 to 1969. He began exhibiting his photographs in 1971. From 1963 to 1982, while living in California and then Vancouver, Rosenberg was a street photographer a term first used by French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson (1934-2004) to describe an emerging genre of photography that focused on the reality of everyday life. In 1982, Rosenberg moved to Nelson where he employed himself as a studio portrait photographer for over a decade. In the early 1990s Rosenberg’s attention shifted away from commercial photography to the pursuit of his artistic practice as a photographer. The photographs displayed here in Gallery B are representative of a period spanning from 1999-2004. They can be seen as a merging of his previous work as a street photographer with that of a portrait photographer into an artistic style and voice that has become Rosenberg’s signature.

Rosenberg’s photography reveals the influence of such central figures in Modern photography as Henri Cartier-Bresson (1934-2004), Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), and Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946). These Modern Art giants believed in art for arts sake – placing the aesthetics such as composition and light in a central position. They also chose to use the everyday world around them as the subject of their work. The movement of the Avant Guard art world from Paris to New York City in the 1950s-60s brought with it liberation for artists from the previous social and political concerns of the war years to an opportunity for artists to personally express their emotions more directly through their art.

In many ways, the Modern art era has a kinship to the Renaissance era (14th -17th century) with the use of a compressed pictorial scene to achieve emotional empathy between the viewer and the subject. We see this in Rosenberg’s compositions; the viewer is drawn in close to the subject as Rosenberg situates himself neither above nor below but on a parallel axis and in this way creates empathy between the viewer and the subject. Rosenberg also places the gaze of his subject outside the lense of his camera; the narrative of the image then lies in the viewer’s ability to project his or her own emotions onto the subject’s gaze. This empathetic episode is what I believe lies at the heart of Rosenberg’s work and we, the viewer, are involved in creating the narrative of the piece.

Critical to understanding Rosenberg’s opus is to remove ourselves from the familiar or provincial perspective of Rosenberg’s photographs and see them from an unfamiliar or non-referential place. The metaphorical nature of his works can then be seen and their lasting appeal as works of art is clear. The photograph of Vic Neufield then becomes Composer or Duncan Grady becomes Veteran, drawing out the universal from its local context. Could we imagine Dorthea Lange’s iconic Migrant Mother as Florence Thompson after holding it in its metaphorical context so richly? If a photographer or visual artist of any media is to go beyond the familiar references of its subject it must transcend this provincial to the universal. Rosenberg’s ability to see this universal in the local is his gift and we the viewer happily recipients.

Rosenberg’s choice of shooting with black and white film is not one of eliminating colour but that of never adopting colour and is in keeping with the tradition of early modernist photography whose focus was one of working within set limitations towards an overall aesthetic. It serves him well to set himself against a post-modern world flooded with media and imagery. Rosenberg’s decision to stay clear of digital processes is intentional so that he maintains a tangible connection to his processes and perhaps to an era of which he fills akin.

With nearly four decades of photography on the streets, Rosenberg’s recently published book Anecdotal Evidence is full of portraits of Nelson characters, opening a door into a world that is at once as small as a moment and as large as a community.